HANGZHOU AND ITS SISTER CITIES

Since its entrance to the international world in September 2013, China’s Belt and

Road Initiative has seen a handful of progress; not only under its pillars of infrastructure

connectivity and trade facilitation but also in terms of policy communication and

people-to-people ties. As of June 2021, 205 documents relating to BRI have been signed

with 140 countries and 31 international organizations. Meanwhile, at the subnational

level, provincial and municipal governments actively engage in economic and cultural

exchanges, regions appealing towards one another on the basis of common

development goals.

One of the subnational forms of BRI cooperation presently encouraged by China is

City-to-City (C2C) Cooperation, which covers all possible manners of relationships

between local stakeholders at any level between countries. Among the various forms it

can take, bilateral C2C has especially been celebrated as a promising policy instrument

for promoting sustainability governance, an approach we find in the Belt and Road

Initiative project through the Hangzhou Sister Cities.

Hangzhou is the capital of Zhejiang Province and the hub for economy, culture,

science, and education. Endowed with rich historical and cultural heritages, Hangzhou is

known as one of the seven ancient capital cities in China and played a significant role in

the development of the ancient Silk Road. Hangzhou’s strategic location on the East

China Sea made it a natural center of trade. With access to the maritime trading routes,

Hangzhou was able to export goods such as rice, porcelain, silk, iron, gunpowder, and

paper from the city and surrounding area to points on the Silk Road and other, farther

trade partners via maritime trading networks across the Indian Ocean.

Hangzhou’s historical and cultural significance makes it a prominent candidate for

C2C Cooperation, as culture is one of the most pervasive sectors of urban life and this

allows cooperation to achieve its mission more effectively. Nations may have separate

and even conflicting interests, but this does not necessarily hold true for actors at the

lower level, which consist of various local institutions and communities. C2C allows for

easier project replications between cities through increased participation of local actors,

as well as collective action facilitated by institutions and communities of common

interests. The pervasive character of culture in everyday life renders them as potent

tools to raise community awareness towards key local development issues, with

extensive campaigns that could reach out to different target groups; a truly valuable asset especially to promote City-to-City Cooperation in an expansive developing region

with diverse national identities.

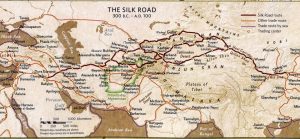

HISTORY OF THE SILK ROAD

The Belt and Road Initiative covers vast expanses of land and sea territories: the

land “belt” runs from China through South and Central Asia into Europe, while the

maritime “road” connects coastal Chinese cities with Africa and the Mediterranean.

Without a sense of common identity to bind them, it is difficult to imagine how various

countries, each with their values and interests, could come together for cooperation. Yet

according to Constructivism in international relations theory, relations between

countries are shaped not simply by material factors, but also by ideational factors that

are historically and socially constructed. These ideational factors are largely affected by

cultural perspectives between cities and countries, which formation could only be

understood by studying their historical background.

With a history of more than 2,000 years, the Silk Route in China can be dated back

to the Han dynasty (207 BCE – 220 CE) in ancient China, where ambassador Zhang Qian

brought treasures from China such as exquisite silk to be presented to rulers in the

western regions as a gift of goodwill. In the following years in history, many great figures

had contributed to the development of the Silk Road, including Alexander the Great,

extending the network until it finally reached its peak during the time of the Byzantine

Empire in the west. The Silk Road’s extensive reach was an important variable in the

development of the civilizations of China, Korea, Japan, India, Persia, Europe, the Horn

of Africa, and Arabia, opening long-distance political and economic relations between

the different civilizations.

On the other side, the Maritime Silk Road is most often associated with the history

of Admiral Zheng He of the Ming Dynasty who conducted seven great naval expeditions

between 1405 and 1433 to establish diplomatic relations and encourage tribute and

trade with states in South-East Asia, around the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf and the

Red Sea. Zheng He’s ships carried Chinese treasures such as silks, porcelains, and other

precious gifts to trade for exotic products of the Indian Ocean. The presence of the

powerful Ming navy led to the emergence of state-directed commercial activity in the

maritime world that extended from Ming China to the Swahili coast of Africa,

stimulating the movement of people and goods across the Maritime Silk Road and

paving the way for a new global market. All in all, the ancient Maritime Silk Road

presented a rich and varied cornucopia of goods and experiences, attracting the

movement of peoples and creating a unique multi-cultural mix for hundreds of years

and allowing for countries in the Indian Ocean, South-East Asia, China, and the Far East

regions to thrive.

THE SILK ROAD HERITAGE

Both the Land and Maritime Silk Road contributed greatly towards the

development of civilization within the region, leaving cultural trails of urban life in cities

across the region as well as a grand narrative of progress and connectivity between

strategic places which could transcend even national interest. This narrative is reflected

through the architecture, art, and cuisines developed in particular cities and regions

affected by the ancient travelers’ route; precious cultural heritages that are often

considered as gateways to tourism resources. Stories of Zheng He’s Voyages, for

example, became widely celebrated today as the symbol of peaceful envoys in both

China and countries along the Maritime Silk Road. Museums and artifacts appear

around the region as a reminder of the great period of exploration, cartography, and

navigation, as well as the influences they left behind.

The impact of the ancient Silk Road, however, is not only a matter of historical

narrative as it also affected the diverse backgrounds of people living in the region today.

One prominent example of this cultural assimilation could be seen in the Chinese

Diaspora phenomenon brought about by Chinese emigration towards cities throughout

the Maritime Silk Road as people followed the trade routes and developed business in

their new destinations. The first major wave of Chinese emigration began in the late

15th century, as trade with South-East Asia expanded. The Chinese settled in lands to

the south: Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, the Malay Archipelago, and Thailand.

When the state relaxed restrictions on travel in the mid-18th century, a second wave of

emigration created large Chinese towns all over South-East Asia. During the next

hundred years, a million people left southern China, mostly heading for places that

already had Chinese settlements. Cultural assimilation easily took place between these

settlements and their surrounding areas. Intermarriage became a common practice and

often led to a rich cultural mix, as can still be seen in Malacca and Penang.

Today an estimated 40 million people of Chinese descent live outside China and

form vibrant business communities, yet their ancestral ties left a cultural heritage

similarly pertained in their land of origin as well as strong social and trade networks.

The presence of local actors in the city with similar areas of interest with stakeholders

abroad paved the way for cultural diplomacy and generated potential advocates for

particular goals of City-to-City Cooperation. So where the historical narrative of the Silk

Road provides cooperation grounds by the approach of idealism, its cultural and

demographic heritage within communities in different countries encourage local

cooperation by appealing through specific cultural identity and interests.

WHAT HAS BEEN DONE SO FAR?

Supported by a strong historical narrative and a robust cultural and demographic

heritage, it is easy to realize the potential for City-to-City Cooperation in the BRI region

and expect such advances to be implemented between Hangzhou’s Sister Cities.

However, a glance at historical precedence reveals that there have not been many

strong and purposeful strategies applied through these instruments on behalf of the

Belt and Road project. Take for example the interactions between Hangzhou and its sister cities in Asia,

where the effects of the Chinese Diaspora is most prominent. Since 1979 to this day,

Hangzhou has developed relations with seven sister cities in Asia, namely Gifu, Fukui,

and Hamamatsu in Japan, Yeosu and Seogwipo in South Korea, Baguio in the

Philippines, as well as Kota Kinabalu in Malaysia. However, there has been minimal

media coverage on activities between these cities and Hangzhou, especially in terms of

development cooperation. Accounts of cooperation have mainly revolved around

diplomatic visits, emergency aids, and exchanges in education, culture, and other areas,

yet the outcome from these activities are only disclosed to society in vague general

assessments and leave ambiguous results in terms of development progress.

Activities between the cities have also in large taken a general and multilateral

approach, often in the forms of conferences and seminars, such as the Hangzhou

International Sister City Mayors Conference in October 2017, where mayors from

around the world held insightful discussions on urban development and cooperation

based on the concepts of innovation, harmony, sustainability, and sharing. On the other

hand, the BRI Initiative also has its local cooperation network through the Belt and Road

Local Cooperation (BRLC), which is committed to integrating the Belt and Road Initiative

into exchange and cooperation among local governments with various practical

exchanges and cooperative programs and activities. However, BRLC activities thus far

appear to be centralized and provide only knowledge assistance for economic

development, such as in the forms of E-Commerce training and workshops.

Therefore, Hangzhou’s efforts in consolidating C2C Cooperation with its BRI sister

cities are roughly deemed insufficient, as they appear to be either too fragmented in

their cultural approach or too centralized in a way that does not directly address their

Silk Road heritage.

This contrasts, for example, with the approach used by the European Union’s

International Urban Cooperation (IUC) program, which is a long-term strategy to foster

sustainable urban development in cooperation with both the public and private sectors,

as well as representatives of academicians, community groups and citizens. As part of a

region sharing a common history of World Wars and their aftermath, European

countries are highly attuned to the need for sustainable development. It is through this

spirit that many local actors are persuaded to contribute to sustainable development

studies. IUC offers cities the opportunity to share and exchange knowledge with their

international counterparts in C2C Cooperation initiatives, building a greener, more

prosperous future. IUC activities also directly support the achievement of global

development goals such as the Sustainable Development Goals, thus results of each cooperation project between cities could be effectively measured and transparently

publicized to the public audience.

All in all, the IUC through over 81 city pairings has worked on a variety of themes

and contributed significantly to the Sustainable Development Goals. This is possible not

only by appealing towards the construct of collective identity and interest through the

European Union but also by establishing the urgency of building upon this heritage by

encouraging all elements of urban society to partake in the process of advancing their

history. Ultimately, the achievements of the IUC could only be made possible through

the engagement of multiple local stakeholders within cities, supporting the formulation

as well as the implementation of each development plan.

In comparison, despite having displayed similar awareness towards the

significance of local involvement, the BRI seems to be struggling to establish such

ventures between Hangzhou sister cities in an organized manner. A key challenge

frequently observed here is the linguistic barrier to communication with local actors,

which becomes a much larger threat due to the diverse ethnicity and languages within

the BRI region. Furthermore, the BRI region is not well-supported by any integrated

institutional infrastructure, such as the European Union, to support such initiatives. This

leaves another need for strategy in cooperation.

CONCLUSION: WHAT NEXT?

We have seen that City-to-City Cooperation provides an innovative approach

towards development by allowing higher engagement with local actors, cultures, and

characteristics and that it is especially effective when supported by a strong historical

narrative and a robust cultural and demographic heritage. The Belt and Road region is

thus well-suited for City-to-City Cooperation as it stands upon an over 2,000 years old

historical narrative of the ancient Silk Road which contributed greatly towards the

development of various cities and civilizations across the region and left behind trails of

both cultural and demographic heritage in its wake through the movement of people,

such as one we see with the Chinese Diaspora.

China has understood this potential and established City-to-City Cooperation

initiatives in the form of Hangzhou sister cities, yet their activities still appear to be

either too fragmented in cultural diplomacy or too centralized in a way that does not

directly address their Silk Road heritage. Efforts at furthering relations are also generally

concentrated only between stakeholders of political and economic influence. There is

minimal media coverage on cooperation progress and achievements, which reflects

poorly or none at all in the eyes of the general society. Not to mention, communication

between stakeholders of the BRI region has always been a challenge due to the diverse

native languages within the region; a problem that is exacerbated by the absence of a

dominant international institution to coordinate between stakeholders across the

region and provide a common information platform, such as one we see in the case of Europe’s International Urban Cooperation under the European Union. Lack of

substantial news to the people could cause interactions between sister city officials to

appear not driven by any purpose beyond political diplomacy. To the incognizant public,

it merely seems as though the city of Hangzhou is used as a “symbol of diplomacy” due

to its reputation as a hub in the Silk Road, whereas inhabitants of the city that formed

the identity in the first place are not given any real opportunity to contribute towards

the continuation of the Silk Road narrative, thereby hindering local engagement in

City-to-City Cooperation initiatives.

If Hangzhou wishes to establish fruitful cooperation relations with its sisters, it

needs to enhance coordination with existing international associations in the region,

such as ASEAN and UCLG, and develop a transparent and widely accessible information

network regarding the initiative’s progress to minimize communication barriers and

increase engagement with local stakeholders. In this way, efforts of appealing towards

historical narratives and cultural heritage between cities could be celebrated and

responded to by both leaders and members of local society. Let us not forget that

regardless of the grand expeditions and political policies of the past, it is the small

everyday exchanges between travelers and local merchants in different cities that had

truly kept the ancient Silk Road alive and brought its success in advancing civilizations

across the region. The Belt and Road Initiative’s success could only be built if the biggest

and smallest members of society move together.

About the writer:

Josephine Emmanuel , Bachelor student on Urban and regional planning, Bandung Institute of Technology and research Intern at the UCLG ASPAC Secretariat.

REFERENCES

Belt and Road Local Cooperation (2018), UCLG-ASPAC Committee on the Belt and Road Local

Cooperation (online), available at:

https://www.brlc.org.cn/2020-03/19/0ba7b278-19ce-48c5-a64f-eec7bebec342.pdf

(22-08-2021).

Council of Europe (2015), City-to-City Cooperation Toolkit (online), available at:

https://rm.coe.int/c2c-city-to-city-cooperation/1680747067 (22-08-2021).

International Urban Cooperation Programme (2018), ‘Fostering Sustainable Urban Development

on a Global Scale’, International Urban Cooperation Programme (online), available at:

https://iuc.eu/fileadmin/templates/iuc/lib/iuc_resource//tools/push_resource_file_resource

.php?uid=az6LEtJt (22-08-2021).

Jung, H. (2019), ‘The Evolution of Social Constructivism in Political Science: Past to Present’, SAGE

Open (online), available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244019832703

(22-08-2021).

Lin, C. (2015), ‘Zheng He and the Maritime Silk Road’, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture

(online), available at:

https://u.osu.edu/mclc/2015/10/02/zheng-he-and-the-maritime-silk-road/ (22-08-2021).

Reid, A. & Homerang, J. (2008), ‘Introduction: The Chinese Diaspora in the Pacific’, The Chinese

Diaspora in the Pacific (online), available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334634622_Introduction_The_Chinese_Diaspora

_in_the_Pacific (22-08-2021)

Top China Travel (2004), Silk Road History: Learn Stories on the 2000-year Old Silk Route (online),

available at: https://www.topchinatravel.com/silk-road/silk-road-history.htm (22-08-2021)

Winter, T. (2016), ‘Heritage Diplomacy Along the One Belt One Road’, The Newsletter (online),

available at:

https://www.academia.edu/26353837/heritage_diplomacy_along_the_One_Belt_One_Road

(22-08-2021).

World Tourism Organization (2019), The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road – Tourism

Opportunities and Impacts, UNWTO, Madrid, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284418749 (22-08-2021).

Zhang, H. (2021), ‘Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative Slowing Down?’, The People’s Map of Global

China (online), available at:

https://thepeoplesmap.net/2021/06/21/is-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-slowing-down/

(22-08-2021)

Feature Image retrieve from https://www.volkansadventures.com/history/the-silk-road/